09 Feb, 2024 Final reconciliation – a lengthy explanation of a pathway

This article explains says things I avoided saying the past few years because tensions around ‘governance’ as it pertains to The Treaty / Te Tiriti were still brewing, and the exact position of the dividing line in viewpoints wasn’t yet clear.

The below isn’t a small thought. While few might read it, it summarises decades of thought. It isn’t short – but there are reasons for it. For any who do read through to the end – you’ll then see the various strands pulled together.

If tensions around Te Tiriti / The Treaty are ever to be reconciled I believe it will be specifically because of the involvement of Christians. This is to say, the way forward will come from character and values, not legislation. The specific need is for grace.

However, I also believe a practical resolution of Treaty matters is needed – not only a spiritual and personal freedom for each individual from grief and pain related to past things.

I believe a clear end-point for Treaty negotiations and claims can exist – but only by God’s grace. This is a huge point. This would include a level of restoration of both mana-whenua (the mana of the land) and mana-Māori (the mana of Māoridom) – reaching a point in which Māori can again forge their own path rather than feeling like victims, dependent on others to help them stand or to feel sufficiently whole or ‘validated’.

To complete my ‘introduction’ to this lengthy holistic articulation – which I suspect very few will ever read: Regarding what likely most-shaped my thinking – it was Matua John Komene who taught at Laidlaw College in the early 1990s. I’ve held a clear view on The Treaty / Te Tiriti for the 30 years since. I’ve rarely shared my thoughts because (a) few were interested in the topic and (b) my thoughts were possibly a bit radical in earlier years. (They no longer are). I suspect Matua John influenced me more than I realised.

(John Komene was a respected Ngāpuhi kaumatua from Kaikohe – and also an outstanding gospel preacher. He travelled the world as an evangelist. In his later years he’d attend hui most weekends, gaining opportunity most times to preach the gospel via speeches or religious services because of his mana. He came to lecture at Laidlaw College where I chose to learn from him across my three years there. He was a man of truth, grace and love.)

I believe the Church holds the keys to a resolution that the Government will never achieve.

Context first:

Examples of the confusion we now face

(If this illustration makes you feel uncomfortable, don’t give up reading. Please discover my point. These few little stories are a platform for a point you may not see coming).

I sit at a Waitangi Dawn service on Waitangi day as a younger Iwi leader politicises the occasion, supporting all things Labour while criticising the current Government. As many as 6 following speakers tautoko what was said. It was foolish and biased – yet done out of ignorance. They suggest the Government want to diminish, ignore and remove the Treaty / Te Tiriti. This isn’t the case. The entire conversation was a ‘straw man’ argument – even if repeated on 1000 platforms to the point of feeling it must be true.

The poor National MP then gets to speak. There is clear tension. He says very little – being both new to the role and I suspect insufficiently acquainted with the stories of our history to speak in a way that imparts belief and hope.

The opposition MP then speaks – celebrating the ‘balanced’ history education she believes the prior Government created, that gives full voice to certain Iwi spokespeople (selected by those who control the funding), and to no others. Those who have studied history feel the weight of this.

NZers are not taught anything yet regarding where their cultural values enabling the levels of prosperity, freedom, equality and charity we have came from. Only one aspect of our history is taught – and I celebrate that it is! I have personally been involved in creating history resources. I truly do celebrate our prior Labour Governments decision – and yet they didn’t endorse the teaching of NZ history. Only a first component of it was empowered!

In a speech at the dawn service the Crown is told it’s doing wrong, and that it has responsibility to lead. But in the next sentence the Crown is told it doesn’t need to be involved and should ‘get out of the way’ because we Māori can be the solution for ourselves.

- I’m not sure how many noticed.

Regarding emotional health I point out that any solution in which I am dependent on the actions of another to be whole, is unhealthy. A person in prison can feel free – while a person who is free can feel as-if in prison. I love this nation; I honour the Treaty / Te Tiriti; I value our history – and what I saw on that day saddened me. It was emotionally unhealthy. It was an emotive movement – in danger of being detached from the truth and justice it thought it was standing for.

So, where was the good? And what is my point?

There was good – and WHERE that good was found is my point!

The MC spoke with grace – and I know him to have strong Christian connections. Also the pastor who shared the word / message spoke with all grace. It was amazing.

My point is that Christians bring a different Spirit – and it’s very clear in these circles, again and again, hui after hui, Waitangi Day after Waitangi Day!

>>> Christians bring hope!

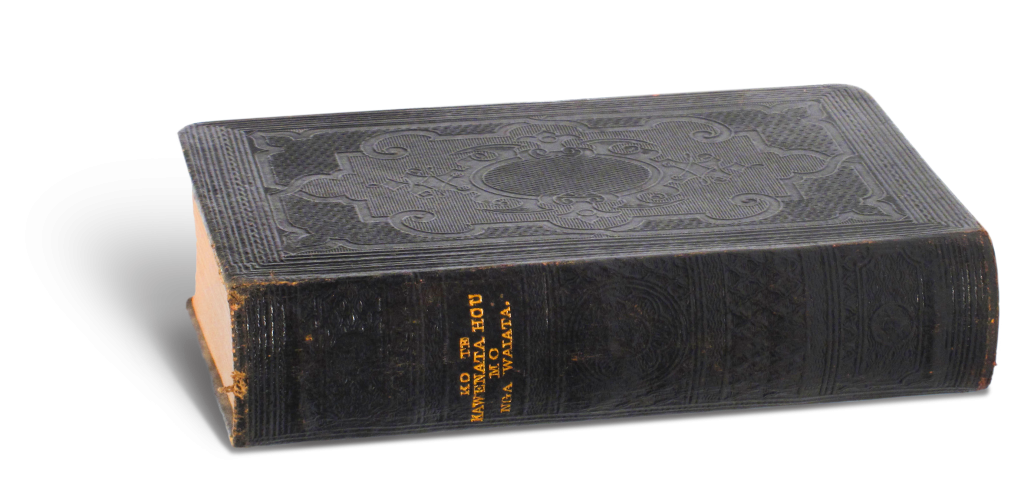

Christians in Britain sat behind the British component of this treaty. The Christian message here had shaped cultural dynamics and values amongst Māori making space for a Treaty to protect Māori. Christians on the ground here also negotiated and represented this hope-filled effort, and it only gained traction because Māori trusted them (the missionaries).

Back at the Dawn Service I then observe how people treat each other afterward. On this occasion it was the National MP who was on the ‘out’ amongst the tensions. Who would even speak with him? I watch as the pastor speaks with him, and another Christian involved in organising the occasion – but I suspect few others did (I left before I could observe further). The patterns are clear.

>>> Christians bring peace and reconciliation – despite differences.

Any non-Christian watching could feel and see the difference – were their mind and heart alert rather than their emotions ‘rising to fight against anyone who disagreed with them’.

The same seemed true of the speeches up at Waitangi that year, as broadcast online.

>>> Christians instinctively build bridges.

So how do we actually build racial harmony?

>>> Our nation needs to allow the Spirit of Christ into this space!

>>> (If we do not do so, division is a tool in the hands of a ‘socialistic’ leader. It can be leveraged for power. Many are uninformed about these things. A cause can even be ‘sincerely supported’ – but not because of the cause; instead because of the division it causes – which is useful for other purposes. This has been done many times in history. These are the ‘useful idiots’ of socialism. My assessment is that most who haven’t read history cannot comprehend how two-faced and deceitful some political leaders can be. We hear our cause supported, and readily believe it to be sincere. We don’t see the bigger picture. Enough said.)

The problem of an ever-moving goalpost

Illustration: “WHY DOES SHE ALWAYS WANT ME TO CHANGE”

It is said that men usually marry with the hope their wife will never change – but she does. Women marry on the assumption their man will change – and he doesn’t.

As a man, were my wife to have an endless list of ways she hoped I’d change, that would bring tension to our marriage. It would be draining, and I’d naturally pull back from her relationally and emotionally over time as a result.

It’s the same with the Treaty. If the assumption is (a) that Pākehā don’t understand – maybe because their skin colour also affects their brains, and (b) if the end goal isn’t clearly defined, it’s going to be a never ending tension. What’s changing in NZ is that many NZers now realise this. Yes, the hurts ran deep – but if we consider family dynamics to illustrate the point, when someone near you holds onto a past hurt and can’t let go of it, its draining for you and them, and it’s going to undermine the health of your relationships.

There needs to be a clear goal. There needs to be a clearly defined end-point. We then address it! And none of this is easy!

The problem of blame

The Bible says children should not be held responsible for the sins of their fathers. To point the finger of blame at people of one race because people of that same race did wrong in our history, is wrong. As a non-Māori, I can tell you that I’ve not felt welcome on Marae a number of times. I’ve felt judged. I’ve had no one talk to me. The anger is real – and it’s increasingly being projected at people on the basis of skin colour. I unfortunately have authority to say this, but that story is best not told.

(Concurrent with this, there can be remarkable grace from within Māoridom. On an entirely separate occasion, I was the recipient of undeserved grace. It is impossible for one article to cover all nuances. I am speaking broadly here, regarding the trends I see in play).

The anger at Europeans will need addressing eventually – and I believe the Spirit of Christ will yet-again be key to it.

The problem of widely ranging expectations around Te Tiriti / The Treaty

We also need to protect our culture from ‘over-enthusiasm’ and errant understandings of what the Treaty guarantees. For example, Te Tiriti doesn’t imply all NZers need to know Te Reo – even while Māori and all others desiring to speak the language are free to speak Te Reo in the public square. I’d suggest being bicultural is instead about being comfortable within two different cultural environments, with an appreciation of small differences in protocol that might exist. So, the goal isn’t church services that are half run in Te Reo – to push the point. It’s about respect and recognition – allowing freedom for all. Within that environment of freedom, people then come together – and embrace the differences, while giving grace to the same differences, learning about each other’s cultures – even while still being of their own.

The problem of bad leadership

Leadership is always about leadership through change, taking the people with you. I don’t want to be political, but I think it true to say that the prior Government failed in leading NZ through change. It instead had an approach of ‘dictating’ its changes through the use of power (legislation leveraging a majority) ‘…because it is right!’ – rather than by leading. These are the values of socialism, to give it a name. Their failure was to bring the people with them. This very-specifically then created a context for division – whether intentionally or not.

It’s possible to have a good goal but a wrong approach. I suggest this is what happened. If changes are forced upon a people too quickly, it is only natural that there will be a reaction. I personally think it was dumb. They will say ‘they don’t care – because by our opinion it was right’.

It created a divisive situation.

Sometimes we have to go backwards before we go forwards.

Two areas that need a reconcilliation

I see two areas from The Treaty / Te Tiriti that need addressing – in terms of wrongs that have been done. One is land / the whenua, and the other relates to self-governance / rangatiratanga.

1. RECONCILING THE TAKING OF THE WHENUA (Mana-Whenua)

The way to ‘compensate’ as a part of an apology is simple. Give money or land.

Re what is given to Māori in Treaty settlements, these are stated as ‘full and final settlements’. Amounts given are small compared to what was lost. Acceptance of these is more an expression of grace from Māori than of generosity from the Crown. What was taken can never be returned and the wrong never put right. There can only be sincere apology – with the need for forgiveness for Māori so matter doesn’t need to continue forever.

The words ‘full and final’ are important – noting my illustration of a wife wanting her husband to be different.

Settlements are therefore an aid to healing. They cannot bring the healing!

Only Māori can do that, and it is a matter of the heart. It is specifically a matter of forgiveness.

But how do you love if you haven’t known love? How do you forgive if you’ve never experienced great forgiveness? Other religions are not the same as what we have as a nation. Christianity holds the keys. Where does this great power for reconciliation come from? We love because he (God) first loved us. We forgive because we have been forgiven.

In speeches on days like Waitangi Day, the words of Christians sometimes contrast with those of non-Christians like ‘chalk and cheese’. One group speaks with vision and hope – while the other with anger and the pointing of the finger. Some, while calling for reconciliation, feed division by nature of an argument which all blame is on the other, as also all the effort required to fix the problem.

Christian Māori and non-Māori alike speak with the same spirit.

We are the glue!

The Church has a role to play here

- …telling the stories

- … helping people see a different future.

2. RECONCILING THE TAKING OF RANGATIRATANGA (Mana-Māori)

This second component was not discussed so much 30 years ago – because we were only then beginning to address the taking of the land.

This second component is not guaranteed in the direct words of the Treaty – but instead in its assumptions. Hence the phrase ‘principles of the Treaty’.

The recognition of high level of self-Government amongst Māori is inherent to the Treaty / Te Tiriti. This sits within the recognition that the chiefs would still be great (tino rangatiratanga) – even while what they retain is all under a common national law (Government / Article 1). How do we ‘settle’ this? What does their ‘greatness’ infer in today’s world?

If we can agree something guaranteed was taken – the way to compensate is not as easy as with the land.

(It is alternatively possible to agree something was taken – but that the Treaty didnt’ guarantee a protection of that particular thing. Therefore, on a legal basis, no recompense is due. This would be no different to the way that most injustices in history have worked out – with someone losing).

These comments will require careful thought, and also grace to not take quick offence or opinion – to instead consider the entire picture painted.

- With 30 years of thought, this is my concluding understanding – with the current confusion and divisions in view.

How do we make right the loss of a potentially high (though undefined) level of self-Government Māori were guaranteed to have – all while still sitting under a common national law (Article 1) – as per Article 2 of The Treaty / Te Tiriti? To articulate the problem: Because chiefs governed their communities on their land – as the land disappeared, so did the context of the village / Pā from which they governed. The involvement of Māori in the national Government / Parliament was also unequal and this was unjust – being a clear breaking of the third article of the Treaty (which guaranteed equal treatment for all).

I suggest this is where the idea of ‘co-governance’ has come from. Co-governance isn’t inherent to Te Tiriti / The Treaty – except in the sense that all would be equal and would therefore have equal opportunity to be involved in decision-making .

As already noted, that didn’t happen.

As a side point – while co-governance isn’t in the Treaty (noting instead a side-reference to an assumed high level of self-governance on one’s own land under the common national law), co-governance can however be a part of a solution in a given context. For example, the returning of a national park to Iwi, which that Iwi then manages in partnership with the Department of Conservation. To note it, in this context the word co-governance therefore refers to the management of specific assets – as contrasted with a national Governmental level of authority.

Co-governance is therefore a partial solution to the problem of restoring a potentially high level of ‘self-governance under the common law’, because the context required for that ‘self-governance’ to be real is now gone!

To summarise again – because the ideas here will be new to many (and may not match the current emotive rhetoric many will easily be caught up in): The treaty – in Article 2 – talks about ‘the great chiefs’ – clearly implying an understood retention of a high level of their mana – even while this is all still under a common national law as is made clear by Article 1 (as also by the nature of the guarantee from the crown of equality in Article 3 – which unavoidably presumes there must be an crown authority over the context within which that guarantee takes place) .

For some humbling clarity on the context

- Britain were the unquestioned global superpower, and everyone knew it – even if some didn’t like it.

- They were also arguably the most-benevolent superpower in history – because Christianity was in the process of ‘infiltrating’ their ranks. This is why we have the Treaty / Te Tiriti! To note it, nearly every people-group that exists has been conquered and/or colonised at some point in history. If we could choose the perpetrator of our own ‘conquering’ – as difficult as this can be to hear – I’ve read many times the comment that England would be our first choice. This doesn’t, however, justify the warfare and conquering spirit that practically all of our various ancestors had – including the English. (Māori weren’t conquered also – they were instead subjugated following the betrayal of an agreement).

- In 1840 various Māori chiefs could see the writing on the wall. Even Ruatara, on the ship with Marsden in 1814, had commented on his fears that the Pākehā might one day come and take over entirely. He knew Māori civilisation was small and weak compared to the might of European civilisation he’d just witnessed.

History isn’t pretty.

- What was proposed in the treaty was a difficult decision for the chiefs because bringing another authority into your land is a big deal. It’s all about trust!

- We concurrently cannot forget that the need for a decision had reached a point of necessity – which is why it was happening. Māori were going to lose potentially everything if they didn’t have this treaty. They were struggling under the unruly behaviour of various Europeans who had settled here – most of whom were English. They had been unable to establish common law and order – let alone to control the behaviour of these new settlers. Many land disputes now existed – and even Europeans on the trading ships were also well-armed. With England not interested in colonising New Zealand (to note the point) – they were concurrently suffering the threat of colonisation from French at Akaroa, and by the Dutch further north. Māori society wasn’t yet unified sufficiently to establish the systems of law and governance necessary address these national-scale challenges. It was a very difficult situation.

Here are some additional reflections – that also bring a context to what was being guaranteed

- Māori abilities in bringing Government were decades shy of anything comparative to what Britain could bring. I once read the comment, ‘If the treaty had been attempted 30 years earlier it would never have come about – while if it had been attempted 30 years later it might have worked.’ Many Māori chiefs were hardly even a decade out of a culture of tribal feudalism (fighting). There was – as yet – no ability to bring about national unity, or a national rule of law. The ‘Te Wakaminenga’ (confederation of Chiefs) was a significant movement. It was achieving notable things. Many chiefs were uniting. But this needed more time – and time is what they didn’t have!

- Regarding Government and sovereignty – we have to accept that the meaning of words has been changed to mean various things in recent decades. The word ‘sovereignty’ is the primary one causing and feeding confusion around The Treaty / Te Tiriti. Sovereignty infers unrestrained authority – with nothing over it. Given that Article 1 gives Britain authority to establish a national Government the chiefs clearly didn’t have ‘Sovereignty’. I know that statement will upset people because it counters current popular rhetoric. But the logic is simple – only unless we change the meaning of the English word ‘sovereignty’. While ‘Rangitaratanga’ can infer sovereignty, the actual word for sovereignty is Kingitanga – and all words need interpreting in their context.

- Why wasn’t Kingitangi used in Article 1? One reason is because there was a Queen on the throne, necessitating the word Kuinitanga – which may not have carried the same sentiments. This is but one small point though. A wider study on the use and meaning of words in that time, including comparisons to He Whakaputanga – the Declaration of Independence, is needed.

- The wider meaning of ‘Rangitiratanga’ includes leadership, autonomy to make decisions and self-determination.

- With the context considered, I suggest the unspoken ‘guarantee’ to chiefs by way of the word selection in Article 2 was “a HIGH LEVEL of independence to rule their own people on their own land – under the common national law.” If the treaty is viewed as a whole, I suggest this is clear.

- Inherent to the guarantees of the Treaty / Te Tiriti it’s clear that national law would affect areas like trade (purchase of land being an example), international trade, taxation / economics and criminal law. What was being guaranteed was therefore a ‘level’ of self-determination in the context of common (shared) national laws. For an easy example, consider a local councils regional jurisdiction in a province of our nation– while sitting under a common national law. There can be jurisdictions of authority under a wider-reaching authority.

- Regarding the meaning of words I note that, just as managing a business is the exercise of the authority of the owner of that business, governing a land is the exercise of the authority of the Sovereign.

My conclusion is therefore quite radically in favour of giving much more to Māori – while defining a clear goal and end-point and limit – but does not including giving completely independent self-Government to Māori, because that the national authority clearly went to the crown (Article 1). This is the context within which Article 2 is then written. I personally believe this to be a simple and clear matter.

How then do we return this ‘self-governance’?

For an example of a principle: Consider the Government declaring all education was to be in English. The Chiefs would have spoken up to say, “No – we want to educate in Te Reo Māori”. Had justice been justice, I believe their autonomy to continue to educate in Te Reo Māori would have been allowed. At no point prior had they agreed to surrendering their language!

The problem is therefore that a process was never put in place to create the 1000 sub-laws needed to define what the Treaty / Te Tiriti meant in practice.

If we can accept Māori autonomy to educate their own on their own lands… …we have the basis for considering a wider picture – and also its limits.

I suggest that all things under ‘Welfare’ could plausibly have been left with Chiefs – governing their own people on their own land – even while under the common national law.

I.e.

- Health

- Education

- Oranga tamariki / intervention in significant family problems or cases of abuse

- Possibly the passing on of (management) of welfare checks to those in state care / support / unemployment.

- Potentially some of the ‘policing’, applying law and justice – though only in line with the common national law on each matter.

To give all this to Iwi would be very messy, and difficult.

I simply talking about what might be just – and not just. Navigating the mess is the Governments problem.

This is about defining the plausible limits of what is and isn’t guaranteed.

To note our context, Māori are already being given the option of ‘governing’ their own people in many of these areas – including the Māori schools movement, health care centres, and the taking over of responsibilities for their own people currently managed by Oranga Tamariki.

Regarding how the finances of this are administrated – recognising the principle of equality for all is fundamental to who we are… there could be an ‘opt in / opt out’ system for Māori to a health system. The Government then funds the health-care provider at a per person rate. The idea isn’t impossible – even if very messy.

- What is defined here honours the agreement we made – while defining needed limits!

Concluding statements

I suggest the above honour the ‘spirit’ and principle of the treaty. It addresses the need for a restoration of both mana-Māori and mana-whenua.

It also clarifies the primary point of current confusion around ‘sovereignty’ – which is important to get behind us (eventually) – because it is the fuel of division.

It also gives us an end-point, saving us from a never-ending tension – as per my illustration of a wife who wants her husband to change in a never-ending list of ways. Non-Māori can be freed from the feeling of an ever-changing goal post.

Māori could also be freed from the ‘conviction’ and ‘jail sentence’ that the ‘victim mentality ‘ our Treaty process creates is for many of their people. Any person who places their value and hope and future in the hands of others is a slave. While there is a natural process here, the only hope for Māori rests with Māori – with or without any recompense or recognition from the Government. Nothing the Government does will EVER heal a person. That’s not how healing and wholeness work!)

And so we come full-circle. Where does healing come from? Where is the end to this process of grief?

The healing is received the moment a person embraces the choice to forgive! It is that simple – and all of our Treaty processes have almost nothing to do with it.

While an apology can be useful, there are many who’ve suffered sexual violations, who’ve received apologies, who aren’t healed. There are concurrently others who never head any apology – who are healed and free!

Who, then, will bring the reconciliation?

It’s not the Government. It is those who carry the Spirit of Jesus!

To take us back to where this article started – this is evident every time a Christian speaks on a Marae, or at a Waitangi event. The difference is clear!

Without Jesus there would be no Treaty, and no conversation to be had.

Without Jesus, a culture of war, revenge, infanticide and human sacrifice would have continued amongst our Celtic ancestors England – let alone amongst Māori here!

Without Jesus there would have been no missionaries with a message of peace – because many amazing values we have here today aren’t actually from European culture – they are from ‘Jesus culture’/ (The pre-Christ Celtic, Nordic and Germanic tribes were no different to pre-Christ Māori – with both good and bad in that picture).

Jesus is the one who makes the difference that matters most!

May God’s Church arise as peacemakers and storytellers, building bridges, sharing hope, bringing freedom!

Other blogs by Dave Mann on this general topic

View full list (including previews) HERE or topical list below from oldest to newest.

- 2017 – A reason to celebrate Waitangi Day!

- 2017 – Article – Biculturalism – more important than most think

- 2017 – New illustrated Treaty of Waitangi series launched

- 2018 – Article – Te Tiriti of Waitangi – How to overcome bicultural mistrust

- 2018 – Article – A vision of our bicultural future

- 2019 – Article – The need to keep our bicultural story honest

- 2019 – Article – How to ensure de-colonisation doesn’t become de-Christainisation

- 2019 – New illustrated NZ history story for ages 4 to 7, titled The First Kiwi Christmas

- 2020 – Toward a reconciling of the Maori and Pakeha church (What happened and what can we do?)

- 2021 – Bicultural or multi-cultural (some terminology for our conversations)

- 2021 – Overcoming threats to the bicultural journey of the New Zealand Church

- 2021 – Why and how local church leaders could engage better with local Māori

- 2022 – An observable process in reconciliation of Māori with the wider Church

- 2022 – Matariki – What it is, and how we might ‘lean in’

- 2023 – God in our history (A journey to work to preserve)

- 2023 – Values not vindication (The solution for poor wellbeing outcomes is in values – not the Treaty)

- 2024 – Amidst bicultural tension – we stay on the journey

- 2024 – Is it wise to tell stories of grief?

—

Other Resources:

A: 5 self-print bulletin-booklets for your church

- Called ‘Then and Now’ – about outreach and our early bicultural story, to give to church members with the bulletin over a 5 week period here (These booklet also encourager support of the Hope Project – which takes some of these stories to the public square).

B: An easy-to-read option to educate yourself, elders, children’s and youth leaders – and then all members (children, youth and adults)

- Consider the illustrated novel series: ‘The Chronicles of Paki – Treaty of Waitangi Series’. These can be found at BigBook.nz. View a blog with displaying some of its endorsements here.

C: Waitangi weekend sermon outlines (free)

- ‘Three Treaties’ (Gibeonites, Waitangi and Jesus) from Dave Mann is (word doc) here, with power point here

- Waitangi Weekend sermon – ‘Leaving a legacy’ – edited – with thanks to Keith Harrington (word doc) here

- Waitangi Weekend sermon – ‘Joshua and the Treaty (five treatise)’ – edited – with thanks to Keith Harrington (word doc) here.

DAVE MANN. Dave is a networker and creative communicator with a vision to see an understanding of the Christian faith continuing and also being valued in the public square in Aotearoa-New Zealand. He has innovated numerous conversational resources for churches, and has coordinated various national nationwide multimedia Easter efforts purposed to open up conversations between church and non-church people about the Christian faith and its significance to our nation’s history and values. Dave is the Producer of the ‘Chronicles of Paki’ illustrated NZ history series created for educational purposes, and the author of various other books and booklets including “Because we care”, “That Leaders might last” and “The Elephant in the Room”. Married to Heather, they have four boys and reside in Tauranga, New Zealand.